Research has always been fascinating to me. It is like diving into a root system, never knowing which way you might be led, then climbing back up until you find a new pathway to explore. This blind-research is quite common in our digital society; the internet is a rhizomatic network of nearly infinite possibility. Starting with a rabbit hole, disguised as an email, you resurface a couple hours later having discovered a landmass that used to sit between the UK and the Netherlands, or looking at animated gifs of cats playing poker. I suspect that it is all relevant in creative research, if we are to hold firm in our belief that Art mimics life.

God made the Earth, but the Dutch made Holland.

As Shorelines is inspired by the North Sea Flood of 1953 which caused deadly storm surges in the UK, Netherlands and Belgium, I have begun to research the cause and effects of this storm. To gain a better understanding of the foreign geography of the Netherlands, I thought it best to begin with research into the history of the land and water that is the Netherlands.

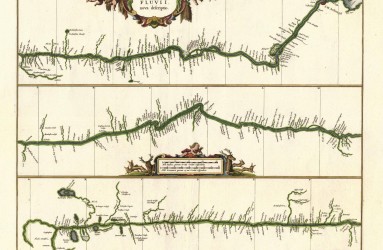

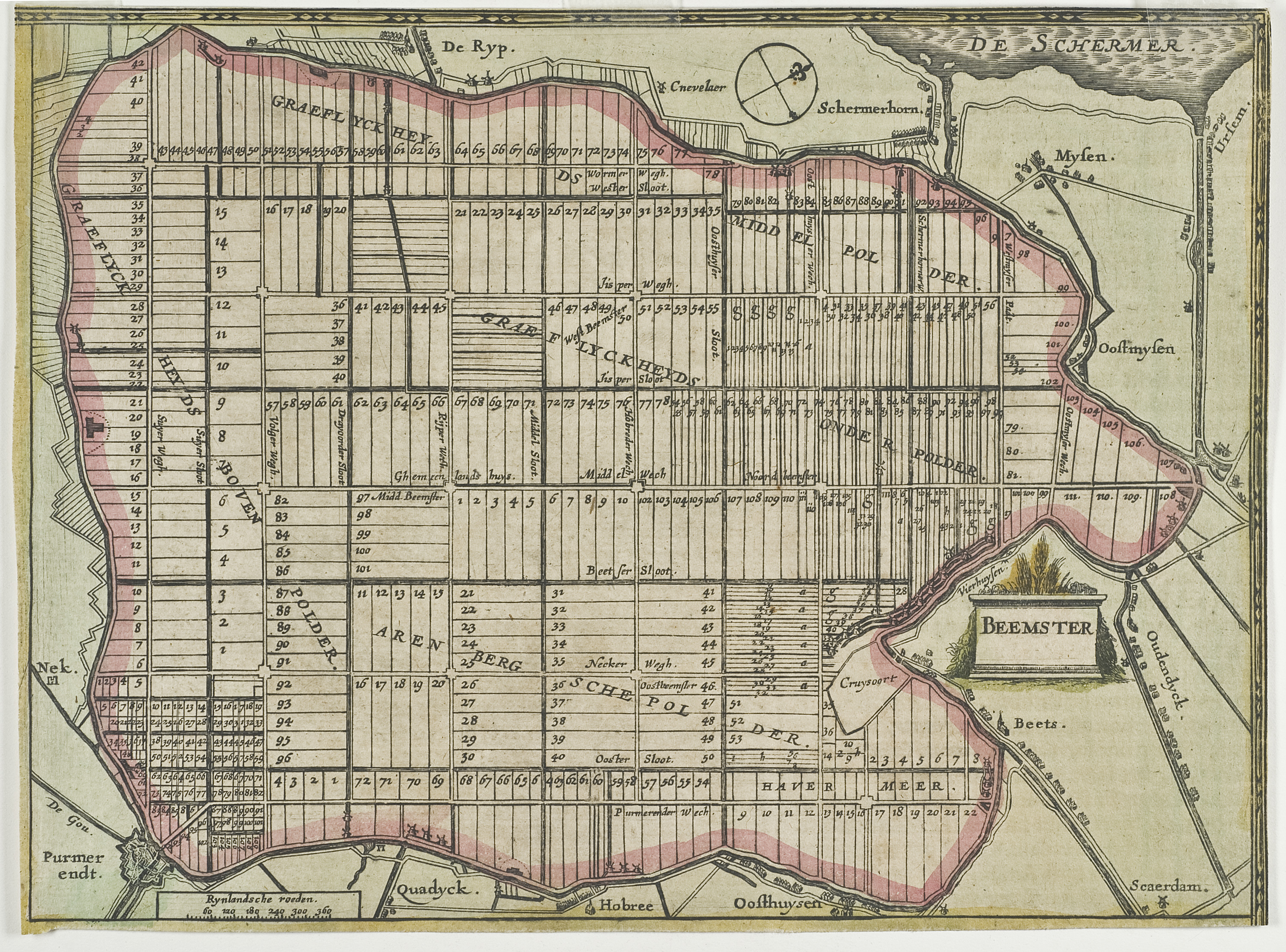

Today, I have been mainly researching the historic floods of the UK and the Netherlands. From the very start of inhabiting the Holland and Flanders, people have been finding ways to control water. What used to be an archipelago amidst peat marsh has now become a more solid landmass, due to water levels receding, but also due to human intervention and manipulation. While it was dangerous to live and farm on the coast of an unpredictable sea, the clay soil was much better for agriculture than the peaty soil further inland. With the sea level fluctuating the first inhabitants at the coast, had to find a way to secure their homes and the crops by building on artificial hills (terpen) which not only protected their home from flooding but also created a barricade from drowning the cultivated fields. Eventually these terpen, connected together as the population grew and became the first dikes around the 9th Century. Advancements in hydrology over the years saw the building of sea dikes and inland dikes to prevent flooding, but also the draining of the peat marshes by irrigation ditches and later windmill pumps. The landscape of the Netherlands was now becoming dryer and more inhabitable due to the ingenuity and drive of the population. Dikes, canals, polders, and windmills are some of the defining characteristics of the Dutch landscape, reminding us of the ever present danger of reclamation by the sea.

Below you can see two maps depicting Beemster, the first so-called polder. One of Beemster as a lake and the next the municipality planning of streets and canals:

Floods have often affected the Netherlands and Belgium throughout history. Reclaimed lands have become part of the sea once again, only to be drained once more a century later. It is a tale of ever changing geography. Flooding even became a strategic military defense. By flooding lands which had been drained, the military could prevent the enemy from closing in, or could destroy the land which the enemy wished to take. It seems a tumultuous affair living below sea-level.

As the climate shifts and sea-levels rise again, the Dutch are continually thinking of how they can prepare for an uncertain future. Only 50% of the Netherlands is at least 1 meter above sea-level and while they have mastered how to control the water they must begin to prepare their flood defenses for a potential rise of 80cm in this century. Since flood defenses began being built, there have always been people charged with their upkeep. As the defenses became more complex committees were organised to look after and develop the dikes, polders, and canals. In the mid-20th Century there were 2,700 Water Control Boards, which have now been amalgamated into twenty-seven. These democratic committees function outside of the government as hold their own elections and levee taxes, ensuring that the reclaimed land that the Netherlands inhabits continues to sustain its population and industry. The energy and expertise that goes into maintaining a nation in such a delicate balance between land and sea is incredible.

Living in Scotland, the thought of living below sea-level is almost unimaginable, constantly walking up hills and seeing mountains in the near distance. Living below sea-level brings to mind an image of looking up to water, as opposed to my reality in Scotland of always looking down upon it. A walk down to the shore of Loch Long, as the clouds began to drizzle, allowed some space for active reflection.